COMP4350/8350

Sound and Music Computing

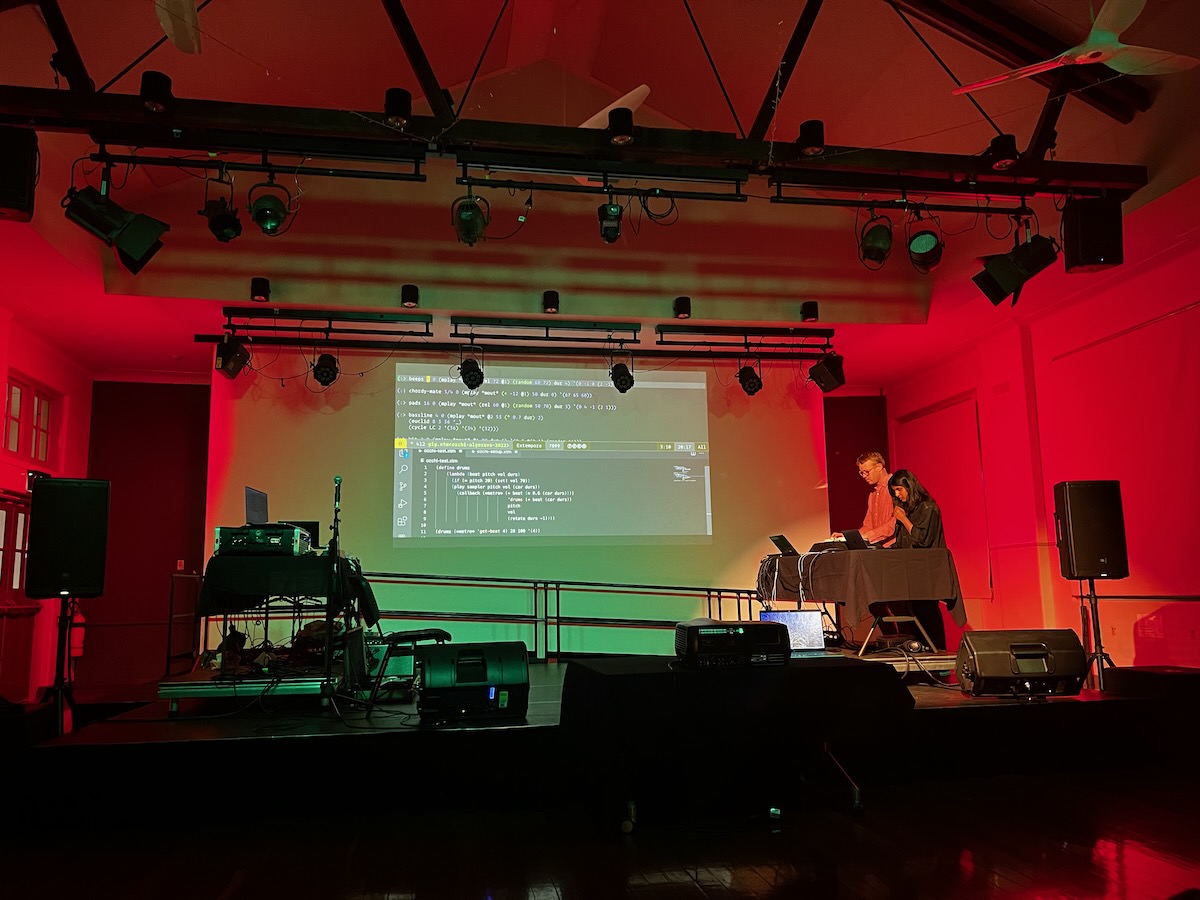

Live Coding

Dr Charles Martin

Outline

This is a pivot point in the course where we re-learn computer music with a text-based programming system.

All the work you have done so far will be reinforced by seeing it in a different way!

It’s important to remember that visual and text programming have different advantages, both are valid ways to complete the course.

What is live coding

Live coding is any form of programming where you can modify the code at the same time as the program is running.

In terms of music, the program represents an ongoing musical process, that is, it defines, schedules, and executes organised sounds.

This leads to interesting program language design and implementation decisions, particularly around representations of time.

Live Coding Music

Live coding is also a performance idiom: a way of creating and enjoying computer music/art by improvising with code live (rather than setting it up before and palying back a pre-prepared program.

An influential group of researchers called TOPLAP wrote a manifesto in 2004 that suggests “code should be seen as well as heard”.

Live coding history

- hacking Perl in night clubs

- Tidal history

- SuperCollider

- ixi

Live coding present

- Strudel

- Gibber,

- Extempore (?),

- Glicol,

- Sema (or whatever those folks are doing these days, the ones where you make your own DSL)

- sonic pi

Learning Live Coding with Strudel

Strudel is a programming system for making computing music in your web browser.

Developed by Felix Roos and Alex McLean. “New” (circa 2022), under active development, based on the existing Tidal Cycles system.

Start using it at strudel.cc.

Strudel is about Patterns

Strudel is focussed on patterns (sequences) of musical events. It provides two important features:

- A compact but expressive syntax for patterns called “mini-notation”.

- Functions for transforming patterns dynamically

"60 62 64" // this is pattern in mini-notation

"60 62 64".note().sound("piano") // this pattern is transformed into notes and synthesised with a piano sound

N.B.: The dot notation xxx().yyy() in Strudel can be interpreted as chaining functions together.

What are patterns made of?

Tidal and Strudel attempt to create a “pure functional representation of patterns”

Pure functional reactive programming.

Read Roos and McLean (2023) for more.

Let’s try out some different sounds

So far we can sequence a simple pattern like:

note("60 62 67 64").sound("piano") // the more conventional notation.

We can change the sound easily by replacing piano with another sound or sample.

Try sine, supersaw, triangle, gm_koto, or pipeorgan_quiet_pedal

Hint: there’s a list of synths and samples In the “sounds” tab of the REPL. Some of these will take a few seconds to load.

Writing Patterns in Mini-Notation

Mini-Notation is a custom language for writing rhythmic patterns with few characters. All of your sequences in Strudel are expressed in Mini-Notation!

"<g3 b3 e4 [a3,c3,e4] [b3,d3,f#4]>*2"

Mini-notation uses strings with special punctuation to represent complex looping sequences. Unlike a step sequencer, you can change the rhythm inside a sequence and make dramatic musical changes with few edits.

Cycles

Strudel (and Tidal) have a built-in concept of speed called “cycles”.

The default speed is 0.5 cycles per second.

There’s no “default” subdivision for cycles (so quite unlike hardware drum machines that might have 16 steps in a sequence).

You can have as many event in a cycle as you want. Patterns can have different cycles-per-second settings (by using the .cpm() function), and patterns can be set to different relative speeds.

Mini-notation: Events and Rests

Mini-notation defines patterns as space separated lists of events. The events can be a number, name of a sample, name of a musical note.

"c d e f g a"

"60 62 64 65 67 69"

The symbol ~ or - is used to denote a “rest”, that is an event in the pattern with no action, e.g.:

"60 ~ 64 65"

"65 67 ~"

Each of these patterns is squished into one cycle! The duration of each event is 1 cycle divided by number of events in the pattern.

Mini-notation: Sub-sequences

You can create sub-sequences within a step with square brackets [ ]:

"[c d] e [e f g a] b"

In this example, the cycle is split into four equal durations.

The durations of events inside [ ] are split again. This lets us subdivide durations.

N.B! Subdivisions don’t have to be multiples of 2!

Mini-notation: Playing two things together

You use commas , to denote events that should occur simultaneously. It’s useful to combine this with [ ].

E.g., you can create chords:

"[c, e, g] [d, f, a]"

Or two parts in one pattern:

"[c d e g a], [c2 g2]"

Mini-notation: Speed adjustments

You can speed up or slow down a whole pattern

"[c d e f]*2" // twice as fast

"[e f g a]/3" // a third of the speed

"[a b c d]*1.01" // a teensy bit faster.

Here’s a neat example with two sequences:

note(`

[e f# b c#4 d4 f# e c#4 b f# d4 c#4],

[e f# b c#4 d4 f# e c#4 b f# d4 c#4]*1.01

`).sound("kawai")

N.B: backtick notation for multiline mini-notation.

Mini-notation: Long and repeated events

There’s shortcuts for defining long events (@) and repeated events (!):

"c d@2 e" // the "d" goes for two divisions of the cycle

"c!2 d e" // the "c" is repeated.

Mini-notation: Events that alternate

It’s more useful that you might initially imagine to have events and sub-events that alternate each cycle.

You can do this with angle brackets < >:

"c d e <f g>" // the last even is either an f or g

This is very useful for determining longer term variation in between cycles.

Mini-notation: Euclidean rhythms

Euclidean rhythms are so useful that they’re built in.

An event can be followed by a triple (beats,segments,offset) which means it will be expanded into the Euclidean rhythm, e.g.:

sound("bd(3,8,0)") // the iconic example

sound("bd(3,8)") // omit the last parameter if it's zero.

This expands to:

sound("bd ~ ~ bd ~ ~ bd ~")

This works with notes as well as bass drums and with portions of a pattern instead of whole patterns.

Mini-notation: Random choices

You can use | to denote a random choice between multiple events, e.g.,

sound("bd hh [ hh | cp] [hh | sd]")

? randomly turns an event into a rest. You can set the probability with a number after the ? (default is 0.5).

s("bd hh? bd hh?0.8")

Interpreting patterns

Events in patterns can be anything, specific functins interpret them in different ways and support different options. Here’s the main ones you’ll see:

note("c d eb f")

note("60 62 63 65") // "note" supports letter names or MIDI number

sound("casio")

s("bd hh sd oh") // "sound" selects sounds/samples by name.

n("0 1 2 3").s("bd") // "n" is generic index or pattern of numbers

note and sound are pretty clear. n is not. In this eexample, n’s indices select different bass drum samples. We also use n to select scale degrees.

N.B: sound and s are synonyms. note and n are different!

Scales and Notes

Strudel has support for scales by applying the excellent Tonal.js library.

To use scale degrees in your patterns, use n to interpret a pattern as indices and then use the scale function to get pitches.

n("0 1 2 3 4 5 -7 1").scale("C:aeolian").s("piano")

The argument for scale is in the form rootnote:scaletype and the scale types come from Tonal.js l

For me, writing with scale degrees is a much easier way to conceptualise live-coding improvisations.

Do it: Write a pattern

Using some of the examples on the previous slides, create a pattern with MIDI notes, note names, or scale degrees.

Choosing different sounds

Most sounds in Strudel are accessible by changing the argument of sound or s (synonyms), e.g.:

note("[c e g e]*4").s("kawai") // nice piano samples

note("[c e g e]*4").s("triangle") // triangle wave

The default sound

Sometimes you can omit s when you are using the default synth (triangle wave):

note("60*16") // just play with a triangle wave

note("36*16").fm(4) // fm synthesis with the default triangle wave.

You can use parameters and effects to modify sounds as well. We’ll look at this next time, but it’s in the documentation for you to find as well.

Drum sounds

Strudel uses Tidal’s tidal-drum-machines library providing lots of samples and a standard naming convention:

| Drum | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Bass drum, Kick drum | bd |

| Snare drum | sd |

| Rimshot | rim |

| Clap | cp |

| Closed hi-hat | hh |

| Open hi-hat | oh |

| Crash | cr |

| Ride | rd |

| Shakers (and maracas, cabasas, etc) | sh |

| High tom | ht |

| Medium tom | mt |

| Low tom | lt |

| Cowbell | cb |

| Tambourine | tb |

| Other percussions | perc |

| Miscellaneous samples | misc |

| Effects | fx |

The best way to explore these is to look at the sounds tab in the REPL

Choosing drum sound banks

For drum sounds, there are many samples of each type (i.e., lots of bass drums called bd) and you can address them with the bank function.

s("bd hh sd oh") // default samples

s("bd hh sd oh").bank("rolandtr909")

Using bank actually just prepends rolandtr909_ to the sample name.

Drum Patterns

Mini-notation is super useful for describing compact but interesting drum patterns, e.g. (borrowed from the docs):

s("bd*4, [~ <sd cp>]*2, [~ hh]*4").bank("rolandtr909")

This example combines ,, < >, [ ] and * to achieve a classic EDM beat in one line.

Do it: Write a drum pattern

- Create a basic drum pattern with some of the drum sounds available (

bd,sd,hh,cp, etc) - Experiment with different values for

bankby checking what is avilable in the sounds tab of the Strudel REPL

Putting it together

To make more complex music, we would like to have multiple patterns playing together. One way to layer patterns it to use stack:

stack(

note("c e g e").sound("sine"),

s("bd hh <sd cp> hh")

)

Another way is to use $:

$: note("c e g e").sound("sine")

$: s("bd hh <sd cp> hh")

Actually you can use any name before the : so naming lines like piano: or bass: works. Any line with a name starting with _ is not played so you can change the first character to mute a part.

What do we know now

We’ve covered a lot:

- Representing patterns in mininotation

- How to select different sounds

- How to address drum sounds

- How to play parts together

You will get to practice these concepts in the workshops this week where you will start going through Strudel’s tutorials.

Do it: Make some techno

It’s been said that the minimum you need to make techno is drums, bass, a lead synth, and freaky noises.

So your task is:

- Use

$:to create a pattern with different parts. - One part should be drums

- One part should be bass (try notes below MIDI 48 or-7 in a scale)

- One part should be lead (try notes above MIDI 60 or 0 in a scale)

- One part should be freaky noises (find a weird sound and use that!)

You’ll do this again in a Computer Music diary…

Here’s one I made earlier…

Here’s an example I’m not quite happy with that uses a couple of extended concepts:

stack(

n(sine.range(0,14).slow(1.5).euclid(5,16)).segment(16).scale("C:aeolian").s("supersaw"),

n("-7*16").scale("C:aeolian").fm("[2|3|4|5|6]*16"),

s("bd*4").bank('RolandTR909'),

s("hh?0.3*16").bank('RolandTR909'),

n(sine.range(0,5).fast(2.2).euclid(7,16)).s("rim")

)

Not the best, aiming to improve as usual.