Outline#

In this chapter, we’ll first talk about version control, the critical concept behind Git, and why you should learn Git to manage your work. Don’t worry about the technical details for now. Let’s focus on how Git works from a higher level view. The commands in practice will be followed afterwards.

What is Version Control#

Imagine a world without Version Control: When your team is working on a project, teammates upload their work to Google Docs or other similar platforms and share a link to everyone. It might sound okay for a small team, but imagine how chaotic and inefficient it can be when your team has 10 or more members! It would be a disaster to keep track of all files and changes made to them. Besides, you can name files in a similar ways. Cumbersome file names like “xxx-first”, “xxx-final” and “xxx-real-final” wouldn’t help because no one can make sure others won’t make new changes.

To resolve problems like that, pioneers developed wonderful version control systems to make our life easier. A Version Control System (VCS) is a special programme that provides an automatic and effective way to keep track of changes in your project files and directories. It allows you to effectively “save your work” (referred to as “commit your work” in VCS parlance) at selected points in the development timeline, and to view/retrieve the files in the status corresponding to any of these saved points as desired. With a VCS, you can keep remote and offsite backups of your project files and history as well as collaborate easily and conveniently with others.

Besides, individuals can benefit immensely as well. Keeping track of what was changed, when, and why, is extremely helpful if you interrupt the project development and return to it later on, especially when your memory has become fuzzy and unreliable.

As you study at the School of Computing, you will notice many courses have assignments or lab tasks online. You are always given a series of instructions to set up your workspace before getting your hands on the assignments/tasks themselves. But what do these Git instructions actually do? To simplify what these instructions are doing, we can take a look at the overview picture below:

Assume we have a lab task at the right hand side. The lab task is created by your convener and it’s hosted on a remote server. To do this task, we need to first create a copy of it on the remote server because we certainly shouldn’t change the original one (otherwise all other people can see your changes!). This is what “fork” will do.

After forking a remote repository, you can download a local copy to your computer, as illustrated on the left. This allows you to work on the project from multiple locations, such as your home PC or a lab computer. The version control system (VCS) enables you to synchronize changes between the remote repository and all of your local copies. Furthermore, the VCS provides the ability to track your project’s history and revert to previous versions if needed.

Advantage Summary#

Among many advantages of version control, we will find the following particularly helpful:

- Collaboration: facilitates multiple people to work on the same codebase

- History tracking: keep track of the entire history of changes to code and project files

- Error recovery: version control allows you to roll back to a previous working state if bugs or errors are introduced

- Accountability: records who made each change and when each change was made and provides a clear audit trail of contributions

At ANU, the version control systems we use are Git and GitLab.

Why Git and how to use it#

Git achieves a sound balance among speed, efficiency, reliability, and ease-of-use compared to other VCSs. To understand Git and version control, we need to keep in mind a few fundamental concepts:

Repository#

A repository contains a collection of files that are managed by Git as well as the complete history of changes to those files.

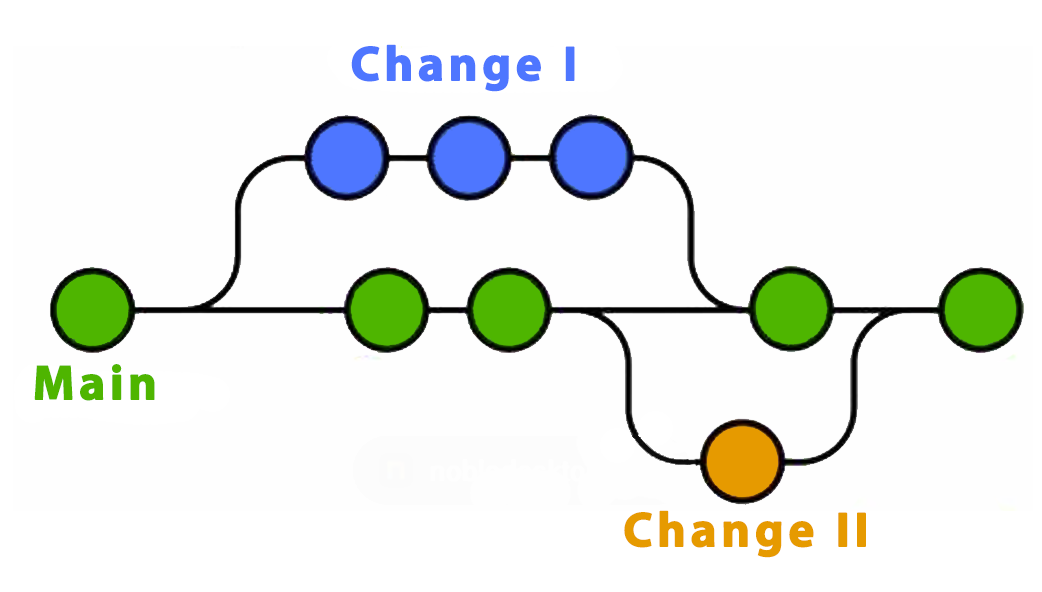

Branch#

A branch is an independent line of development. It allows for separate, isolated work on a feature or bug fix. In industry, engineers always create new branches before they start working, such as adding new features and fixing bugs. Usually, you can take main branch as the final version of your project.

Great! Based on the fundamental concepts above, we can now move on to learn why the first lab task or assignment instructs you to fork or clone a repository.

Fork#

Only you can decide who can touch your repository. Likewise, if you are not the repository owner, you will need permission from the original creator to make changes. But can we create a copy of repositories that we don’t own? Yes, by forking.

To fork a repo is to make a copy of the repo under a namespace that you control. This gives you full control over the new copy of the repo.

In page 4, we will see how to give others privileges to your repository so that they can make changes without having to make their own fork.

Clone#

After you log in to GitLab on your web browser, You may notice that you can directly edit files in your repositories. But imagine trying to program using that interface! Instead, we want to make a local copy of a repo and make changes as we see fit using more powerful software development tools, such as VSCode and IntelliJ. To do this, we make a local copy by cloning.

By cloning a repo, we download the latest version of the repo from the cloud (i.e. GitLab) to our computer. As we make changes, we can use other commands listed below to track these changes and upload them back to the GitLab version.

Git Data Model#

Fantastic! Now we can make changes to a local copy of a repository with a local powerful editor on our computer. At this point, we can be a magician and do whatever we want to the local copy. There are 4 most commonly used commands to start with: add, pull, commit and push. Before we get to know what are them, we need to take a look at an image first:

This image summarises Git’s data model. Git roughly consists of 3 layers: Working Directory, Stage and History. To simply, you may imagine Git as a time machine:

- Workspace is where we actively edit files locally. This is our “playground”.

- Staging Area is a temporary holding place before we commit our work or make a time travel. You can select and prepare specific changes or files to be included here.

- Local Repository is where we store committed local changes. Each commit represents a specific point in the timeline of your project. It captures a complete snapshot of files and directories in the repository. You can think of it as a series of photos that you can explore, effectively enabling you to travel back and forth in time to see the project’s evolution.

- Remote Repository is on a remote server for sharing and backing up your work.

The benefit of this “overcomplicated” model is that it gives you more precision and control over your project’s history. You can avoid committing unfinished or unrelated changes, which leads to a cleaner and more understandable project history. This, in turn, makes it easier to collaborate with others, debug issues, and manage your project over time. Essentially, Git’s 3-layer model helps you work more efficiently and with greater confidence.

After we make some changes to our local copy, we can now manage these changes by using the following commands:

Add#

Add is to decide which files should be tracked by Git by adding into the staging area:

In the page 4, we will explain how to use it in detail with a real example.

Commit#

A commit represents a local snapshot of the project at a specific point in time. After you make some changes, you need to commit those changes to the local repository so that they are ready to be synchronized to the remote repository:

If you wish to commit all changes, git add can be skipped. But running git add is recommended in most cases as it offers more control and allows for fine-grained commit management.

Push#

Pushing is the act of taking one or multiple snapshots (commits) of the repo, each labelled with a commit message, and copying these changes to the remote repository (such as GitLab that we use). Briefly speaking, pushing is the act of taking a save point and uploading it to the online version of the repo:

Pull#

Pulling is the act of keeping your local repository up-to-date with the latest changes from a remote repository.

Let’s say that you want to share your work with someone else after adding, committing and pushing. Your Git repo has added your friend with the correct privileges so that they can edit files on your repo. You send them the URL for your Git repo, and they clone this repo.

Notice that, in this case, your friend does not need to fork the repo first since they want to work on your copy of the repo so that you can collaborate!

Let’s assume your friend doesn’t like your (rushed) version of the README, so they decide to change it. They open a text editor, change the file, and commit their changes with a helpful commit message explaining the changes and why they were made. Finally, they push their commits to your fork of the repository.

The next time you work on the project, your first step should be to ensure that your local version of the repo matches the online version. To do this, you use git pull, which applies any new commits available online to your local version of the repo. Just like a push, a pull requires you to specify a remote and a branch.

After pulling, you will see the changes made by your friend:

Great! You made it to the end! But we are missing one last thing: How about GitLab? If Git can do everything above, why do we need GitLab? What’s the relationship between Git and GitLab?

What does GitLab do#

Just like Git manages your project’s history, GitLab builds upon Git and adds extra superpowers to make collaboration even easier. GitLab is a centralized hosting service for Git repositories. It provides a web-based interface where you can visualize and organize your project’s changes, invite teammates to join, and manage different branches of your project effortlessly.

You can think of GitLab as a centralized keeper of your project. It helps you keep track of who made what changes, coordinate work among team members, and seamlessly merge everyone’s contributions together. Moreover, you can also set up automatic tests with GitLab, ensuring that your codebase always looks its best.

Further Reading#

To systematically learn Git, we have a list of recommended resources which you can dive deeper:

- Pro Git is highly recommended reading. Going through Chapters 1–5 should teach you most of how to use Git proficiently. The later chapters are about more interesting and advanced materials.

- Git for Computer Scientists is a short explanation of Git’s data model, with less pseudo code and more fancy diagrams.

- Git from the Bottom Up is a detailed explanation of Git’s implementation details beyond just the data model, for the curious.

- How to explain git in simple words

Moving on#

Git might seem complicated and hard to learn but don’t be terrified. Despite the abstract definitions of terminologies and concepts, you will gradually get familiar with how to use Git and GitLab by following the chapters ahead. But before we start, we need to learn some basics of Linux to work better with Git.