Professor Hanna Suominen juggles teaching responsibilities at The Australian National University (ANU) School of Computing with Our Health In Our Hands (OHIOH), a strategic initiative of ANU applying advanced computing to healthcare and her duties at the John Eccles Institute of Neuroscience.

She recently welcomed us to her office, and as we were settling into our chairs she mentioned that new satellites are having an impact on healthcare in remote areas of Australia, a major focus of her research.

ANU CECC:You were saying as I got out the audio recorder that they’ve put new satellites where?

ProfessorHanna Suominen:In the sky.

ANU CECC:Well, of course.

Professor Hanna Suominen:[Laughs] Yeah, that’s a silly answer to that. So, we have people living in parts of Australia that are extremely remote. These low range satellites were put up in the sky mainly targeting communications in the US and the Northern Hemisphere. But when they’re asleep, the satellites are here on top of Central Australia.

It’s so remote that it has the best connection, better than Sydney, and it will continue to be so because there are so few people living there.

So for telehealth, it’s an outstanding opportunity to help communities there.

ANU CECC:Being far from major cities, they don’t have to compete for satellite signal?

Professor Hanna Suominen:Exactly. That’s the future. We were there for four days without power and network, so that’s the current situation. But I’m excited about the future because I have been working in OHIOH on all kinds of minimally invasive solutions that are accessible and easy to take into the field and supposed to make healthcare, excellent healthcare, more equitable.

So, everybody, regardless of where they live or what their socioeconomic status is, can have that excellent health experience that each one of us deserves. That’s what I have been working on for a long time and very intensively for the past six, seven years as part of the OHIOH challenge.

ANU CECC:What are the challenges when providing healthcare to people in remote areas, and people who are of lower socioeconomic backgrounds?

Professor Hanna Suominen:The biggest burden is the disease itself. So, for example, people living with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) or Parkinson disease tend to be fatigued. Many of them are elderly. For them to come to a big city to get their brain MRI [Magnetic resonance imaging] done or visit a clinician, it makes them even more tired.

If they happen to have a good day on the day when they come and visit the neurologist, the measurements are going to look fine. And then it’s nearly impossible to capture the signs and symptoms that we are worried about.

So, what we are trying to do is to allow a type of scalable and simple monitoring of the diseases—their signs and symptoms, markers we call them.

ANU CECC:While they’re going about their daily business?

Professor Hanna Suominen:Exactly. So, a smartphone app where you do finger tapping for 30 seconds on the phone. The touch screen analyses whether your pace continues, or if you miss the circles, or if you fatigue and your tapping becomes slower, or if the force that you apply to your tapping changes.

So, you have samples from people without the condition and people who have early signs and symptoms. We can monitor whether or not there is a significant difference in their tapping pattern—is it closer to people without the condition, or people with the condition (and we have quite a few of the latter).

For Parkinson disease, another validated marker is your voice. It’s as simple as saying “aaaaaah” to the microphone. If we analyse it over time, and if your “aaaaah” starts to deviate from the markers that are counted from previous voice signals, that’s a good time to alert your specialist that we need to have a more robust medical assessment done.

ANU CECC:This is great. When can we have it?

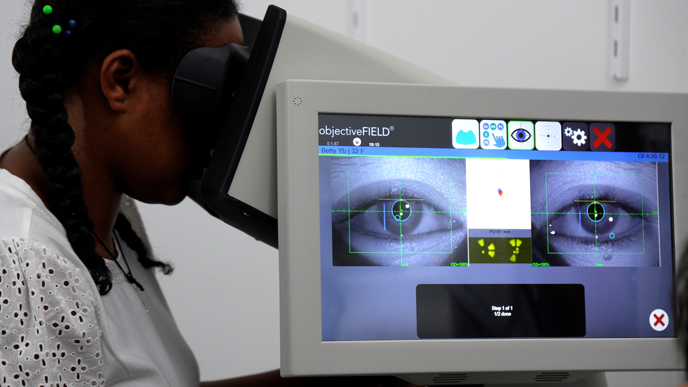

Professor Hanna Suominen:Oh, well, some of our work is going to the market already. So, we have a machine which is called an Objective Field Analyser (OFA). It’s research has been led by Professor Ted Maddess at ANU.

The machine looks a bit like binoculars. You

look into it, and it assesses your brain and your eye health as you

stare at something that I like to call “eyes of an owl”.

The machine looks a bit like binoculars. You

look into it, and it assesses your brain and your eye health as you

stare at something that I like to call “eyes of an owl”.

They are yellow circles that keep on changing a little bit in tone and pattern—other people call it “flowers blooming”—and from this stimulation of the eye, we measure your retina, other parts of the eye and how they move or change with respect to the stimulation, and from that we can assess many conditions. For example, diabetes. There’s some work on neurodegenerative diseases, even migraine, glaucoma. We have a portable version on the way and then we have table-mounted and it’s approved for medical use and it’s being commercialised by our partner, Konan Medical, available later this year.

ANU CECC:Is it the first in the world?

Professor Hanna Suominen:There are a few similar things. But what we do really well is—first of all, our young people with diabetes really challenge us as researchers. We had a 6-minute test and we considered it a lovely meditation session: Just sit there 6 minutes staring at this.

But our young people with diabetes—these

are 14 to 18 year olds—said that is too boring. They challenged us,

and we got it to 82 seconds. So that’s an advantage. That’s first in

the world and secondly, it’s super accurate. So, it’s the best

performing device in the world for sure.

But our young people with diabetes—these

are 14 to 18 year olds—said that is too boring. They challenged us,

and we got it to 82 seconds. So that’s an advantage. That’s first in

the world and secondly, it’s super accurate. So, it’s the best

performing device in the world for sure.

ANU CECC:Great. Did you say migraines? Our eyes tell us something about migraines? How does that work?

Professor Hanna Suominen:In order to get all the clearances done for medical use, we had to study if the test has some side effects. I’m a migraine sufferer myself, and quite often blinking lights are one of those things that trigger migraines for me. So, we needed to check that the device doesn’t trigger migraines or epilepsy or any of these things.

The device can actually tell if you had a migraine quite a long time ago. I like to call it “predicting the history”.

ANU CECC:Did you test it on yourself?

Professor Hanna Suominen:No, no, I haven’t done it myself yet. But that’s a good topic to talk about. We are recruiting participants for these studies and in others that have to do with data analysis. The more data we have the merrier, and we also need healthy control participants. You don’t even need to be fully healthy, but without this target disease.

ANU CECC:Parkinson.

Professor Hanna Suominen:Parkinson, MS, and diabetes, in particular are the neurological conditions that relate to my work at the John Eccles Institute. In order to support early diagnosis, we need to find someone that we call your twin. So, a person who is the same age, the same gender and otherwise similar to you. And the only difference is that this person has not been diagnosed, let’s say with Parkinson.

For example, people of my age, women in their forties tend to be busy in life with family commitments and so on. But that happens to be, for example, for MS, the most common time when you get diagnosed. So, yes, I have volunteered myself and I encourage anyone else to do that too.

ANU CECC: The John Eccles Institute, OHIOH, ANU Computing… a whole bunch of things are listed at the bottom of your email signature. Can you describe how they all fit together and how you have the time?

Professor Hanna Suominen:Well, I’m the happiest when I’m a busy bee. That’s how I have always been. I have always been extremely driven by wanting to contribute to our community for the greater good, in particular with respect to health and medicine. Thankfully, computing and applied mathematics modelling—AI, that is my speciality—can really help and the time is ripe for that. I have been working on this field for a long, long, long time.

When I did my first studies at university, straight after Year 12, it was about medical modelling and computational models to support medicine. That was 25 years ago. My masters thesis touched upon this. Then I did a PhD about large language models—the natural language processing in medicine—using a language that was very under-resourced at the time, Finnish.

I was one of the pioneers who was making web search systems for doctors and nurses in intensive care to find everything in the records written in Finnish that has to do, let’s say, with a patient’s pain status or a patient’s heart or a patient’s breathing.

After that, I did a postdoc here in Australia in one of the world’s best machine learning groups. That brought me here in 2010, and that was the time when I started to work on these smart sensing systems. But that was not for unwell people; it was the peak of our fitness level.

For example, helping our Olympians to swim better, a bit like smart sports watches and wellness sensors are today. But in 2010, I can guarantee that nobody else was working on those heavily yet and the machine learning on them.

That journey brought me here. I joined ANU in 2016. I was attracted by the position statement “to bridge the gap between computing and health sciences”, and I have been doing that ever since.

In 2017, ANU launched the Grand Challenges Initiative, major funding to support transdisciplinary research that brings the campus together. Our Health in Our Hands—where I’m an executive member and also the director of the Big Data and Machine Learning program—we were the lucky first recipients of funding.

And the other part in my signature [Associate Director (Neuroinformatics), the John Eccles Institute Institute of Neuroscience, College of Health and Medicine] also continues my journey.

From March of this year, I have had a joint position between the ANU School of Computing and ANU School of Health and Medicine, specifically helping to nurture and scale the John Eccles Institute of Neurosciences.

ANU CECC:Are there things that you were doing at the School of Computing before March that you now don’t do because of the joint appointment?

Professor Hanna Suominen:I’m not anymore serving this School as its Associate Director (Engagement & Impact). It was a service role for nearly two years, so it was time to come to conclusion anyway.

I feel that I’ve made the portfolio go, so I was the first one setting it up, getting our Computing Advisory Board (CAB) going, coming up with a strategy that aligns and supports the ANU, CECC, and School strategies for engagement and impact. But I care deeply. It’s the storytelling and making people know about the amazing science we do.

Get those portfolios and stories going, and I felt that it’s time to move on and hand it over to the next one. Associate Professor Penny Kyburz is directing the team now.

It’s about having the privilege to be visionary and plan new work and then evaluate the outcomes in the end, but also put dream teams together. And once the team is there, once that foundation is laid, I quite often feel that it’s my time to move on and do something else that is calling for me and bring others along and give them responsibilities, delegate. Same of course in education and research. It’s not only me, we have an excellent and quite sizeable team.

ANU CECC:And all of this on top of teaching as well?

Professor Hanna Suominen:Yes, I have been teaching since 2012 at the ANU. Together with my colleagues from the National Information and Communications Technology Australia (NICTA), we invented this concept of advanced methods in document analysis, machine learning, natural language processing, information retrieval, web technology, social media, anything to do with human language and put a course together. I volunteered to teach at ANU. And that was a very successful initiative.

We got an award from that contribution to education at ANU. I also gave guest lectures to AI, ML, those type of courses. But then when I joined the ANU, I became the convener of Networked Information Systems—a really difficult course to deliver. Very complex, very rich, diverse cohort, which is really good.

But it comes with challenges when you

have both undergrad and postgraduate students from two different

Colleges on a transdisciplinary topic. I have convened it for seven

years and actually last week there was a paper published about

it. Professor Gabriele Bammer from the College of Health and Medicine

brought a paper together about transdisciplinary teaching at ANU at

the undergraduate level and from Computing, that networked information

systems course was highlighted there, and it’s all founded on OHIOH.

But it comes with challenges when you

have both undergrad and postgraduate students from two different

Colleges on a transdisciplinary topic. I have convened it for seven

years and actually last week there was a paper published about

it. Professor Gabriele Bammer from the College of Health and Medicine

brought a paper together about transdisciplinary teaching at ANU at

the undergraduate level and from Computing, that networked information

systems course was highlighted there, and it’s all founded on OHIOH.

So I’m not doing more, I’m using the same for many, many things. My research guides the education that I provide.

ANU CECC:So your teaching will continue no matter what?

Professor Hanna Suominen:Yes. We need to have this next generation of graduates who know how to work across disciplines, across professions, across areas of expertise, work with people—lived experience experts, we call them—in changing the world and changing healthcare. Without them, change doesn’t happen.

ANU CECC:We interviewed a number of School of Computing professors for a video. And it begins with Professor Lexing Xie who says, “When I think about the different things I do for the university, whether it’s teaching, service or the research, I think that the teaching is going to have the most impact 20, 30 years from now. I look at my students and I think ‘they will do great things.’”

Professor Hanna Suominen:That’s exactly right. It’s the legacy and scale. So already with the Networked Information Systems course not touching upon the coursework project students or HDR candidates, just for that course, it’s around 250 to 350 students per year that go through my hands. It’s amazing, when you plant a seed in these people’s thinking and they take it to their careers.

They are some of the brightest people I know, and indeed they have a lot of power. And I’m hoping that some of the work that I do makes people consider that applications of computing to health might be that dream for them, the one for them to follow.

Professor Suominen is part of the ANU-led team who have secured Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF)funding for their project “Closed loop non-invasive brain stimulation treatment for depression”. Led by Professor Paul Fitzgerald from the ANU College of Health and Medicine and featuring Professor Graham Williams and Dr Jess Moore from the School of Computing, the project aims to develop a digital therapeutic device as a home-based and widely available non-drug treatment.

More about The Magic of Machine Learning in Medicine

More about Our Health In Our Hands

Do you or someone you know have lived experience with Parkinson disease, MS, or type 1 diabetes? If you would like to help Professor Suominen and her team progress their work, please contact ohioh.management@anu.edu.au